A virtual Achilles? Teaching ancient worlds through VR

)

Teaching agendas have been recently dominated by discussions about the use of Virtual Reality in education. Schools and universities have been eager to consider the benefits of teaching with VR together with creative ways in which it can help promote meaningful education. Humanities have a very important role to play in the exploration of these benefits. Right now, there are pockets of VR exploration across the discipline but there is little work concerning the teaching and learning of ancient languages and literature, meaning we are still at the very beginning of a long and exciting road of exploring technological marvels that can facilitate the transmission of knowledge about the ancient world.

At UCL there have been several projects relating to existing work on Virtual Reality that have been undertaken in different departments. The project I created hoped to create a springboard of transdisciplinary knowledge exchange between academics, students, and organisations working together on the possibilities of immersive learning about antiquity. In specific, the project addressed ways in which VR can enhance student learning of Classics in the post-Covid era and how it can help meet the increasing learning needs of a diverse student body that wants to study the Ancient World.

The project focused on identifying alternative routes to study Classical literature and languages through VR to enrich the departmental teaching and learning portfolio. It also aimed at encouraging student participation in building secure and learning-efficient virtual environments which advance language learning in a way that the students’ expectations for a high quality blended physical and digital learning experience are satisfied. We wanted to explore ways in which we can develop flexible modes of learning Classical literature and ancient Languages and to support the needs of a diverse body of learners (adult learners, students with learning difficulties or disadvantaged backgrounds, international students, etc.) by widening participation. We also hoped that this would develop interdisciplinary opportunities that will include internal and external collaborations.

Our aim was to understand how to best embed VR teaching in modules and support language-related learning activities (grammar and syntax teaching, scenario sessions, distance and lifelong learning, etc.). The challenges using VR for the teaching of the ancient world were also explored. Digital innovation is an imperative in Humanities, and we have been leading the way to VR teaching and learning by appreciating digital enhancement as an important enabler for the students to succeed.

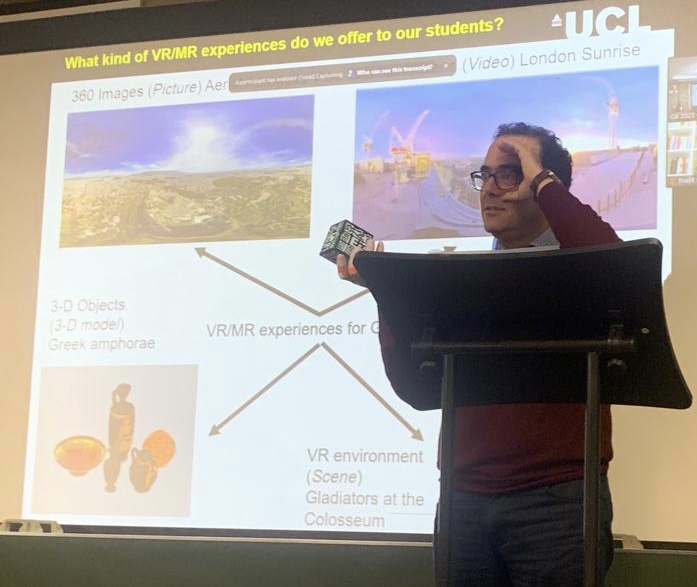

To achieve all these goals, we worked together with Class VR, a company that produces educational VR experiences for schools, universities, and other institutions and that participated last year at Bett. We have bought four VR headsets and a subscription to the company’s service and we have set up a VR office hour during a term in which students tried various VR experiences that the company offers. The experiences are downloaded to a private ClassVR account from a pool of materials that have been uploaded by users and the company on their cloud. Each user can search the keywords they prefer and make a “playlist” of experiences which can then be saved and downloaded to the headsets. The experiences include 4 categories:

- 360 images

- 360 videos

- 3D-objects

- Virtual environments

The 360 images and videos we have used are shots or videos from archaeological places in Greece or Rome that can be downloaded to the headsets as images (usually taken by a drone) or as videos with sound. The 3D-objects are a useful tool for virtual Object Based Learning (OBL). Objects like Greek amphoras or Roman busts are saved on the cloud as virtual objects after having been photographed through a 360 app and then they are downloaded to the headsets. The company provides some rubber cubes to which the virtual objects are attached so that when the user sees the cubes through VR they see, and they handle the virtual object. This allows the tutor to turn any object with either Greek or Latin into a virtual object and download it to the headsets linking the linguistic information to the virtual image.

The possibility of having a virtual museum of objects with Greek and Latin to use in language classes is a very exciting one. Finally, the user of ClassVR can experience virtual environments (called “scenes”) again downloaded from the cloud to the headsets. For example, they can be in the Colosseum watching gladiators fighting or they can explore with the help of a joystick the different areas and levels of the building. Teaching resources (like quizzes or handouts) accompany the presentation of the class.

The feedback of the students was overwhelmingly positive. They found the experience highly interactive, and immersive and suggested that it increased their engagement. They also mentioned that it made them more creative, with focused knowledge and they praised the adaptability of the class (creating different classrooms for different levels, learning from home or in class, with headsets or laptops). Finally, they praised the ability of VR to bring the ancient world into life and to enhance storytelling about antiquity together with its potential to make Classics more accessible.

On the other hand, there has been some scepticism as well. Is this entertainment more than education? Is social isolation of students and tutors dangerous for them? How accessible and expensive is this technology? What about practical problems (quality of graphics, space, copyright, training of students and tutors, time management, etc.)? And finally, are VR classes able to replace real classes and what about health issues (vertigo, dizziness, eye irritation, nausea) that some users have of even comfortability levels? All these are useful and valid questions that every tutor-user of VR must take into consideration.

In conclusion, VR technology can bring the ancient world to life, it can provide new exciting tools to learn ancient languages through virtual OBL or personalised education and it can fuel the students’ imagination and offer new insights about the ancient world. Both educators and companies will have to think carefully about the limitations of VR and how they can maximise its benefits in order to enhance our students’ knowledge and offer the best teaching experience.

Dr Antony Makrinos is an Associate Professor in Classics at UCL. Since 2004, Antony has worked as a Lecturer in the School of English and Drama at Queen Mary University of London and as a Research and Teaching Fellow at KCL and UCL. Since 2012 he has been a member of the Department of Greek and Latin as a Teaching Fellow in Classics, and recently, became a Senior Teaching Fellow in Classics and a Senior Teaching Fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

Dr Antony Makrinos is an Associate Professor in Classics at UCL. Since 2004, Antony has worked as a Lecturer in the School of English and Drama at Queen Mary University of London and as a Research and Teaching Fellow at KCL and UCL. Since 2012 he has been a member of the Department of Greek and Latin as a Teaching Fellow in Classics, and recently, became a Senior Teaching Fellow in Classics and a Senior Teaching Fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

Antony is also a member of EUROCLASSICA and a Member of the Council of the Hellenic Society. For the last 7 years he has also served as the Director of the Summer School in Homer which takes place every year at the Dept of Greek Latin, UCL.

Tags

- ancient

- classics

- different

- downloaded

- experiences

- greek

- headsets

- knowledge

- languages

- learning

- literature

- teaching

- through

- together

- ucl

- virtual

- VR

- ways

- world

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)